Teacher Shortages: How We Got Here and Available Solutions

In January, the Praxis Core basic skills test became obsolete.

The decision, supported by New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, was made to encourage teacher enrollment and address the longstanding teacher shortage. The test’s critics say it’s an unnecessary expense and that new teachers have gone through proper steps to prove their basic skills competencies by completing a college degree.

Eliminating the Praxis Core basic skills barrier is one example of how New Jersey leadership has stepped up to address the teacher shortage at home. Others include forming scholarships for student teachers, creating a task force and implementing three annual job fairs hosted by the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE).

Compared to the rest of the nation, New Jersey sits in the top 10 for states with the fewest shortages, but the full extent of the shortage is unknown, according to New Jersey Monitor in 2024:

“Despite its longevity, the full scale of New Jersey’s teacher shortage remains unknown. It’s unclear whether the Department of Education ever completed a statutorily required annual report on teacher retention that was first due in mid-2022.”

In February 2024, Rutgers University provided more concrete data surrounding shortages. A report from Rutgers University’s John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development found that 10% of teachers leave the profession within the first three years. Additionally, the report found that the number of provisional teaching certificates issued in New Jersey during the 2022-2023 school year dropped nearly 40% from the previous decade.

These shortages may seem sudden and severe, however, they were growing steadily for more than a decade. In this blog, we will dig into when shortages began, why they got out of control and a new solution to increase teacher certifications in New Jersey.

When did teacher shortages start and why?

Economic strife in the early 2000s kicked off drastic education budget cuts, making day-to-day teaching more challenging. As time went on, these challenges became everyday realities and as teaching became more difficult, attitudes began to evolve.

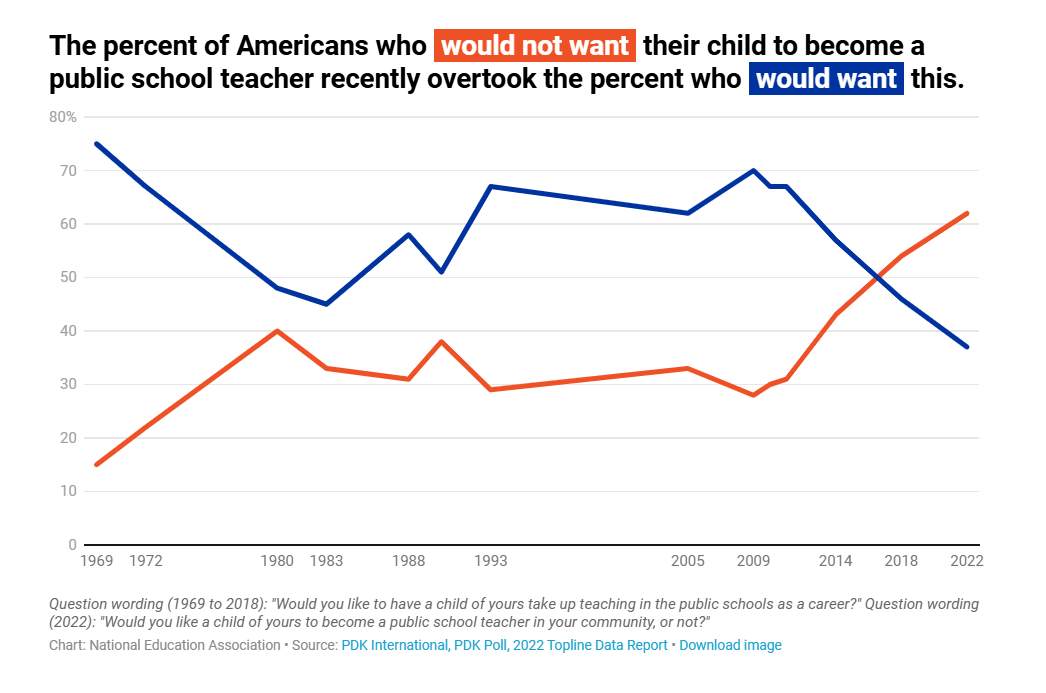

The National Education Association uncovered a trend that could contribute to the growing shortage over time. Over the past decade, the number of Americans who want their child to become a public school teacher has flipped. Now, parents and guardians are more likely to say they would not want their child to become a public school teacher.

This trend began to take hold between 2009 and 2011—right in the middle of the recession—and gained steam around 2013. Parents and guardians are influential, and this discouragement could deter many would-be teachers from entering the profession.

Economic experts also sensed trouble on the horizon. In 2019, the Economic Policy Institute said a ‘perfect storm’ was on the way. Everything from the prior decade was building to a head.

“We argue that, when issues such as teacher quality and the unequal distribution of highly qualified teachers across schools serving different concentrations of low-income students are taken into consideration, the teacher shortage problem is much more severe than previously recognized.”

One year later, a global crisis became that perfect storm.

COVID’s contribution

Education already had cracks showing when the COVID pandemic put extreme pressure on both educators and their students.

Years before “social distancing” entered our vocabularies, the Economic Policy Institute gave us an earlier warning when A Coming Crisis in Teaching was published in September 2016.

The report states:

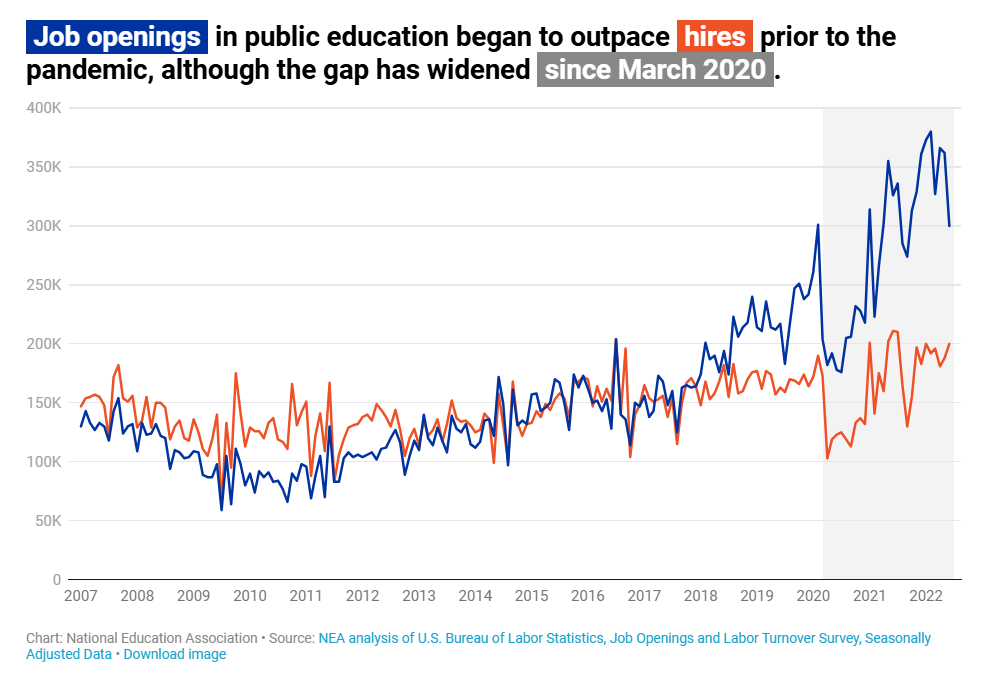

“Combining estimates of supply and demand, our modeling reveals an estimated teacher shortage of approximately 64,000 teachers in the 2015–16 school year. By 2020, an estimated 300,000 new teachers will be needed per year, and by 2025, that number will increase to 316,000 annually.”

According to NEA data, the report is accurate, with 300,000 new teachers needed at the beginning of 2020. New hires, however, did not meet the demand, with only 190,000 new teachers hired.

During this time, teachers were tasked with navigating an entirely new way of learning that limits student engagement opportunities. Already stretched thin, the pressure was too much for many teachers. A 2021 RAND study found that nearly a quarter of teachers planned to leave their jobs at the end of the 2020-2021 school year. The prior average was one in six teachers.

Brookings research discovered three key reasons why the shortage grew during this time:

- Veteran teachers considered early retirement, pulling districts’ most experienced teachers away from schools.

- Having to change instructional modes often increased the probability of teachers leaving.

- COVID health concerns also increased a teacher’s possibility of leaving.

This research shows the importance of structure and personal health in teaching, areas that have been slowly improving since the pandemic began.

Providing solutions in New Jersey

New Jersey legislature has been at work passing bills, funding grants and creating initiatives to help address the teacher shortage, including ParaPreppED.

An NJDOE-funded teacher apprenticeship initiative, ParaPreppED helps districts support college-degree-holding paraprofessionals and substitutes in becoming full-time licensed K-12 teachers. We know paraprofessionals and substitute teachers have a foundational on-the-job-training that makes them great full-time teachers. Now, the path to career growth is easier.

Resources from the Teacher Apprenticeship Network provide additional support for Rutgers Graduate School of Education to partner with districts to promote the apprenticeship, establish new USDOL-approved teacher registered teacher apprenticeship programs, and recruit talent.

Overall, the program aims to:

- Increase the number of Registered Teacher Apprenticeships in the state;

- Expand the teacher pipeline, leveraging the existing district talent;

- Address barriers for aspiring teachers through targeted support like Praxis prep; and

- Conduct and disseminate ongoing research on the implementation and impact of the initiative.

ParaPreppED is driven by the expressed interests of district leaders who wish to identify overlooked or hidden teaching talent among eligible paraprofessionals and substitutes the district can support to fill teaching vacancies, including those in Special Education, Science and Math, and English as a Second Language or Bilingual Education.

If you’re considering following your dream of teaching, Rutgers Alternate Route can offer you the support and training you need to succeed. Be sure to follow Rutgers Alternate Route on Twitter and sign up for Alternate Route’s monthly newsletter for more information and stories from the field of education.

Heather Ngoma has over 25 years of experience collaborating with educators across New Jersey to drive education innovation. She currently serves as the Director of the Rutgers-GSE Alternate Route Program in the Department of Learning and Teaching, a program which helps career changers, recent college graduates, and other aspiring education professionals become licensed teachers in New Jersey. Follow her on Twitter @heatherngoma.

Heather Ngoma has over 25 years of experience collaborating with educators across New Jersey to drive education innovation. She currently serves as the Director of the Rutgers-GSE Alternate Route Program in the Department of Learning and Teaching, a program which helps career changers, recent college graduates, and other aspiring education professionals become licensed teachers in New Jersey. Follow her on Twitter @heatherngoma.